Frans Bosch System, 肌力與體能訓練

衝刺與科學:典範轉移 Sprinting and Science: A Paradigm Shift

Sprinting and Science: A Paradigm Shift | by Frans Bosch

衝刺與科學:典範轉移 | 授權翻譯自螺旋肌力體能學院Leo

Frans Bosch System Level1 國際師資認證課程:https://forms.gle/M2wJNhvH2uo9YZpL9

May 18, 2024

“Sprinting is a science.” This was the maxim of Bud Winter. It’s no coincidence that he carefully analyzed and studied the starting methods of Armin Hary, among others. In the past, Sam Mussabini also attempted to train ‘scientifically’ in his own way. Trainers like Carlo Vittori (Mennea) and Valentin Petrovski (Borzov) each applied scientific methods in their pursuit of better performance. Now, 50 to 60 years later, the picture paradoxically appears vaguer and less clear. Yes, sprinting is a science. But it’s much more complex than one might have presumed. Frans Bosch, a globally recognized consultant and educator in sports, sheds light on the latest insights and developments.

「短跑是一門科學。」這是Bud Winter的格言,這並不是巧合,Bud仔細分析並研究了Armin Hary等人的起跑方法;在過去,Sam Mussabini也試圖以他自己的方式進行“科學”訓練;像Carlo Vittori (Mennea)和Valentin Petrovski (Borzov)等教練,皆在追求更好表現的過程中運用了科學方法,如今,在50到60年後,情況卻顯得矛盾而更加模糊不清。是的,短跑是一門科學,但它比人們所假設的要複雜得多,Frans Bosch是一位全球公認的運動顧問及教育者,他表達了最新的見解和發展。

In recent decades, many scientific fields, especially biological ones, have undergone a dramatic shift away from linear thinking. Instead of striving for a one-to-one connection of cause and effect, there’s a focus on understanding ’emergence’; an organization stemming from the complexity of interconnected subsystems, where the appearance of that organization cannot be reduced to a limited part of those subsystems. In simpler terms, the behavior of the total system cannot be deduced from its underlying subsystems. The whole is no longer the sum of its parts, but the sum of the interactions of those parts, or even the interactions between the interactions, and so forth. With so many interactions and layers, causality loses its connection, yet a coherent organization can still emerge.

在近幾十年中,許多科學領域 (尤其是生物領域),從原本的線性思維,發生劇烈轉變,與其努力尋求一對一的因果關係,不如將重點放在理解「湧現 (Emergence)」上;一種來自相互關聯的複雜子系統所產生的組織,其中該組織的出現無法簡化為這些子系統的有限部分,簡單來說,整體系統的行為無法從其底層子系統推導出來,整體不再是部分的總和,而是這些部分相互作用的總和,甚至是相互作用之間的相互作用等等,隨著如此多的互動和層次,因果關係失去了連結,但仍然可以出現一個一致的組織。

Linear processes, with their cause-and-effect connection, demand a blueprint. In a complex environment, such a blueprint must be adaptive, which inherently makes it fragile. A single flaw in the blueprint can be disastrous. Emergent phenomena don’t face this problem. With interactions between interactions, they’re not only flexible and adaptive but also robust.

在線性過程中,其因果關係需要一個藍圖,但在複雜的環境中,這樣的藍圖必須是適應性的,這本質上使得它變得脆弱,藍圖中的一個小失誤可能導致災難。湧現現象不會面臨這個問題,隨著相互作用之間的互動,它們不僅靈活且可調整,而且也具有韌性。

A crucial condition for robustness is that a system or organism, like a rabbit in its burrow, isn’t easily caught. In more complex terms, an organism is characterized by ‘degeneracy,’ where multiple components with different structures can fulfill similar functions. Thus, there are always multiple routes from impulse to execution. Therefore, from the impulse, there’s divergence, spreading interactions over numerous simple processes, each governed by simple regulatory mechanisms, which aren’t very precise. From these divergent processes and their interactions emerges a coherent whole, the emergent organization.

韌性的關鍵條件是系統或生物體,像在洞穴中的兔子,不容易被捕獲,更為複雜的說法是,有「退化性 (Degeneracy,指在一個限制的情況下,一個集合中的對象改變其性質並且變成比較簡單的集合,例如:點是退化的圓、圓是退化的橢圓,線是退化的拋物線)」的生物體,其中多個結構不同的組件可以執行類似的功能,所以從動機到執行的路徑總是存在多種選擇。也因此,從動機開始便會存在著分歧,在眾多簡單過程中延伸互動,每個過程都受簡單調節機制的控制,而這些機制並不非常精確,從這些分歧過程及其互動中產生了一個一致的整體,即湧現組織。

An athlete in full sprint embodies such a complex process of degeneracy and interactions between interactions. Various routes from the movement impulse to execution interact in such a way that no single one can determine the final outcome.

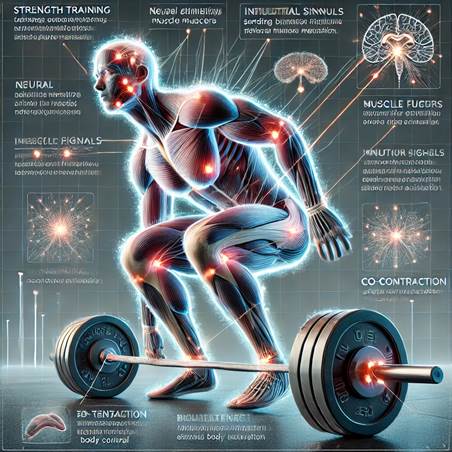

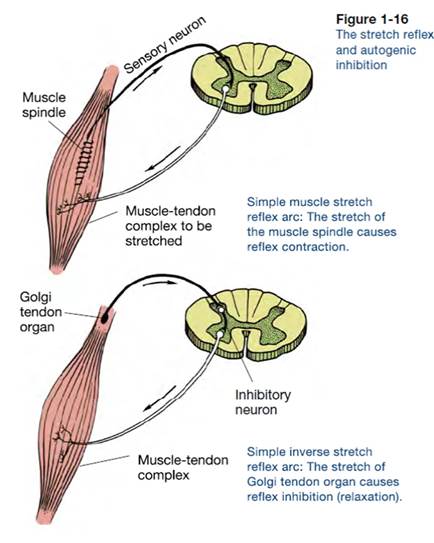

What does the sprinting organism aim to escape (to further extend the analogy with a rabbit)? Sprinting is a boundary load. The sprinter (and their coach) aim to push the limits of the muscle-skeletal system’s capabilities and efficiently transmit maximum forces through the body. However, the body isn’t naturally inclined towards this because pushing to the edge can easily lead to injury, from muscle tears to stress fractures. The evolutionary priority has been to avoid injury, especially in humans. Thus, strict performance-limiting mechanisms (escape routes) are built-in, which are more decisive for the final performance than performance-enhancing factors. For instance, the efferent pathways (those sending signals to the muscles) produce not only stimulating but also inhibitory signals, meaning an untrained individual might only engage about 75% of their muscle fibers in a specific movement pattern. Additionally, biotensegrity and co-contractions, necessary for controlling the body, also have inhibitory effects.

全力衝刺的運動員體現了這種退化性和相互作用之間複雜過程的互動,從動作衝動到執行的各種路徑以這樣的方式互動,使得沒有任何一條路徑能夠決定最終結果。

這種短跑生物體旨在逃避什麼(為了進一步延伸與兔子的類比)?短跑是一種邊界負載,短跑選手(及其教練)的目標是推動肌肉骨骼系統能力的極限,並高效地通過身體傳遞最大力量。然而,身體並不自然傾向於這樣,因為推進到邊緣很容易導致受傷,從肌肉撕裂到壓力性骨折,進化的優先事項一直是避免受傷,尤其是在人類中,內建了嚴格的性能限制機制(逃避路徑),這些機制對最終性能的決定性作用超過了增強性能的因素。例如,輸出神經通路(那些向肌肉發送信號的途徑)不僅發出刺激信號,還會發出抑制信號,這意味著一個未經訓練的個體在特定的運動模式中可能只會參與大約75%的肌肉纖維,此外,生物張力完整性和共同收縮,對控制身體至關重要,也具有抑制作用。

Especially in humans, the subsystems contributing to sprint performance tightly regulate each other through their interactions. Therefore, adding up the positive components contributing to performance at the individual level can overestimate the sprint speed of a top runner. Conversely, taking into account the (dampening) interactions and interactions between interactions (how the components limit each other’s output) provides a more realistic estimation of the top speed achievable. Thus, the performance of a top sprinter isn’t determined by the extremes of the fully operating components but by the inhibitory effect they exert on each other.

尤其在人類中,影響短跑表現的子系統通過相互作用緊密地調節彼此,因此,對於個體層面的性能,將正向組件相加可能會高估頂級跑者的短跑速度;相反的,考慮到(減弱的)相互作用和相互作用之間的相互作用(這些組件如何限制彼此的輸出)提供了對可達到的最高速度更現實的估計。因此,頂級短跑者的表現並不是由完全運作組件的極限所決定,而是由它們對彼此施加的抑制效果所決定。

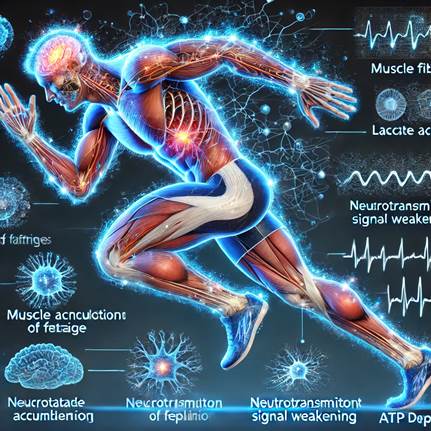

This inhibition makes searching for one or a limited number of underlying causes for performance ability a futile endeavor. These factor(s) won’t be found. Fast-twitch fibers may indeed contract faster than slow-twitch fibers, but do they work better together with the elastic action of tendons? Slow-twitch fibers have better elastic capacity in their Z-lines (the connection between serially linked contracting sarcomeres), suggesting otherwise.

這種抑制使得尋找一個或有限的潛在表現能力原因變得毫無意義,這些因素不會被發現,快收縮肌肉纖維的確可能比慢收縮纖維收縮得更快,但它們是否能與肌腱的彈性作用更好地協同運作?慢收縮肌肉纖維在其Z線(串聯連接的收縮肌節之間的連接)中具有更好的彈性能力,這表明情況並非如此。

Moreover, do these tendons optimally function with the changing levers in the body (joints being complex structures where the axis of rotation often shifts during movement)? This interplay must then be synchronized with ‘muscle gearing’ (the angle at which muscle fibers work changes during contraction, giving muscles a sort of ‘automatic gearbox’), which is influenced by (barely researched) muscle deformation. It’s entirely unknown how these barely studied phenomena should be factored into an overall pattern like sprinting.

此外,這些肌腱是否能與身體中不斷變化的槓桿(關節作為運動過程中旋轉軸經常移動的複雜結構)最佳運行?這種相互作用必須與「肌肉變速」(肌肉纖維在收縮過程中工作的角度變化,給肌肉一種“自動變速器”的感覺)同步,這受到(幾乎沒有研究)肌肉變形的影響,尚不清楚這些鮮有研究的現象應如何納入像短跑這樣的整體模式。

All of this must then align with a given body length and body proportion. This internal organization must, to zoom out further to the larger picture, adapt to constantly changing environmental conditions. Even then, we’re not done. Environmental influences also affect the viscoelastic properties of passive tissues (the complex way tendons behave, for example), and we’re back to where we started, or rather, we’re back to a circle of interrelated factors. As there are cross-connections everywhere in this circle, it becomes more of a tangle of interrelated factors.

所有這些都必須與給定的身體長度和身體比例對齊,這種內部組織必須進一步調整以適應不斷變化的環境條件,即便如此,我們也還沒有完成,環境變數還會影響被動組織的粘彈性特性(例如肌腱的複雜行為),我們又回到了最初的起點,或者說,我們又回到了相互關聯因素的圈子中,由於在這個圈子中到處都有交叉聯繫,這變得更像一個相互關聯因素的糾結。

Inhibition 限制

On top of these mechanical interactions comes the influence of inhibition (inhibition) by the brain based on afferent signals (signals resulting from mechanical interactions that the brain registers), or rather based on the subjective interpretation of these afferent signals (not the signals from the body, but what the brain makes of those signals). This interpretation by the brain is then influenced by socio-cultural factors. To make the Gordian knot even more complicated, genetic influences can be added, but then it must be epigenetic because gene expression is also influenced by environmental factors. That sounds like a complex interaction of interactions, but it’s not even the tip of the iceberg. Physiological and hormonal processes, ‘jerk’ principles, and self-correction in ‘spring-mass’ systems (brief explanation), things that are reasonably understood through robotics today, haven’t been mentioned yet and can further complicate matters.

在這些機械互動之上,腦部基於來自機械互動而產生的傳入信號(信號由腦部發動)所引起的抑制影響隨之而來,或是更確切地說,是基於對這些傳入信號的主觀闡釋(不是來自身體的信號,而是腦部對這些信號的解讀),腦部的這一解釋也受到社會文化因素的影響,為了使這個戈耳狄俄斯之結 (Gordian knot,棘手的問題) 更為複雜,還可以加入遺傳影響,但那必須是表觀遺傳學,因為基因表達也受到環境因素的影響。這聽起來像是一場複雜的互動交互,但這甚至不是冰山一角。生理和荷爾蒙過程、擾動原則及彈簧質點系統中的自我修正(簡短解釋),那些今天透過機器人技術能合理理解的東西尚未提及,並可能進一步使問題複雜化。

Inhibition through interactions between components is thus decisive for performance. Those with the lowest thresholds of inhibition, not only having exclusively A-brand components in their system but also having the least inhibition built-in and a body that’s simultaneously unstable enough to want to adapt to training stimuli (the so-called ‘high responders’) have a chance. In short, those who unite opposing demands of adaptability and robustness within themselves in such a way that they excel at a boundary load: sprinting at high speed.

因此,通過元件之間的互動進行的抑制對表現至關重要,那些擁有最低抑制閾值的人,不僅擁有系統中唯一的 A 品牌元件,而且擁有最少的內建抑制,以及一個同時足夠不穩定以想要適應訓練刺激的身體(所謂的「高反應者」)才有機會,簡而言之,那些能夠在自己體內將適應性和穩定性這兩種對立需求結合在一起的人,才能在邊界負荷下表現出色:以高速衝刺。

The new direction in thinking about training will focus on reducing inhibition, moving away from increasing capabilities. This is a Gradwandelung (in German) elegantly visible everywhere in athletics: from Michael Johnson to Wayde van Niekerk, from Javier Sotomayor to Mutaz Barshim, etc. And as a provisional highlight of that change, Armand Duplantis; not the epitome of great capabilities, but the epitome of minimal inhibition.

對訓練的新思維方向將專注於減少抑制,而非單純提高身體能力,這在田徑界無處不在,優雅地顯示出一種漸進式變化:從Michael Johnson到Wayde van Niekerk,從Javier Sotomayor到Mutaz Barshim等等。而該變化的暫時高光可由Armand Duplantis代表;他不是偉大能力的具體體現,而是最小抑制的具體體現。

Evolution and Outliers演化與離群值

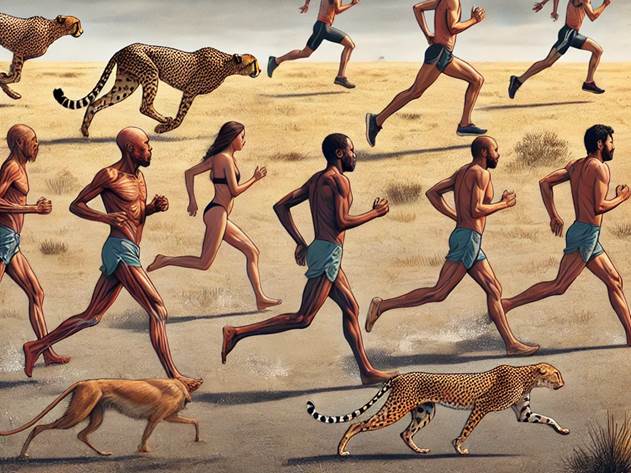

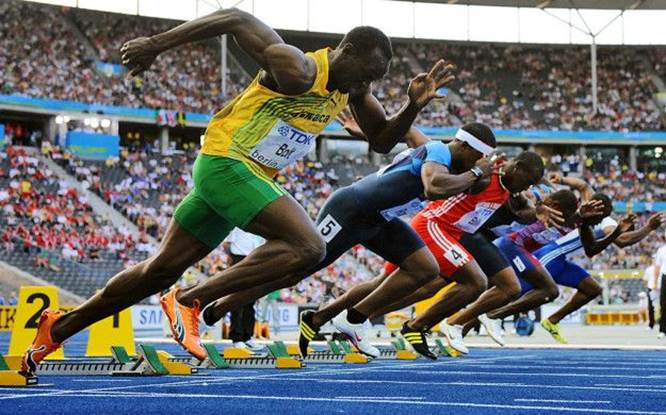

The human anatomy is anatomically not suited for sprinting. There are numerous anatomical features that are nonsensical when it comes to top speed. For instance, the position of the foot relative to the thigh, at a 90-degree angle, results in inefficient energy transfer and limits maximum running speed. Distal muscle mass (mass far from the pelvis, such as in the calves) is cumbersome, a trait even understood better by chickens, turkeys, and especially ostriches than by humans. Humans are not born sprinters but born joggers; that they can do. Sprinting offers no evolutionary advantage because most predators and prey are faster over short distances than humans, hence the inefficient build for sprinting. Usain Bolt’s top speed is a byproduct of characteristics that biologically aren’t particularly useful. And perhaps the dominance of black athletes in sprinting can at least partly be explained by the fact that it is merely a byproduct.

人類的解剖學在生理上並不適合奔跑,當談及最高速度時,有許多解剖特徵是毫無意義的,例如:小腿與大腿之間90度的角度位置會導致能量轉換效率低下,限制最高跑步速度。遠端肌肉量(例如小腿的質量)是笨重的,這一特徵相較於雞、火雞,尤其是駝鳥,人類更顯笨拙,因此人類並非天生的短跑者,而是天生的慢跑者,這是他們能做到的。短跑沒有提供任何進化上的優勢,因為絕大多數掠食者和被捕食者在短距離上比人類更快,因此在短跑方面的生理構造是低效的,Usain Bolt的最高速度是一些生物特徵的副產品,這些特徵在生物學上並不是特別有用的,而且,或許在短跑中黑人運動員的主導地位至少可以部分解釋為這僅僅是一種副產品。

Sprinting is dominated by black athletes. It might be interesting to compare sprinting with other movement patterns that stress the musculoskeletal system at the limits of its capacity. In activities like jumping, also evolutionarily irrelevant, the dominance of athletes of African origin is less pronounced (consider Jonathan Edwards, for instance, the world record holder in the triple jump), and this decreases as the approach speed decreases, from long jump to triple jump to high jump. This phenomenon cannot be explained solely by looking at a single performance determining parameter, such as the widespread idea that muscle fiber type (fast-twitch versus slow-twitch) is everything. Furthermore, pole vaulting, also an evolutionarily irrelevant explosive skill, is predominantly a ‘white’ affair.

短跑由黑人運動員主導,將短跑與其他在極限負荷下施加對肌肉骨骼系統的運動模式進行比較可能會很有趣;在跳躍等活動中,這在進化上也並不重要,非洲裔運動員的主導地位則不太明顯(例如考慮一下Jonathan Edwards,三項跳的世界記錄保持者),而這種主導地位隨著接近速度的降低而減少,從跳遠到三項跳再到跳高。這一現象不能只通過查看單一的表現參數來解釋,比如許多觀點認為肌肉纖維類型(快收縮與慢收縮)就是一切,此外,撐桿跳高,這也是一項進化上無關緊要的爆發性技能,主要是「白人」的事情。

In this context, it is interesting to look at a movement pattern that is evolutionarily relevant and also involves the limit load of forces. Throwing is evolutionarily essential. Being able to throw might have been as significant an evolutionary event as walking upright. Significant adaptations to the structure of the shoulder girdle were necessary to throw hard and accurately. There is no other species that can throw like humans. Look at throwing sports that stress the body to its limits. All ethnicities (white, black, Asian, etc.) produce roughly the same number of top performers in throwing sports (baseball, javelin throwing, etc.), depending on socio-cultural influences, of course.

在這種情況下,看看一種在進化上相關且涉及極限負荷的運動模式就很有趣,投擲是進化上必不可少的,能夠投擲也許與站立行走一樣是重大的進化事件。為了能夠用力且準確地投擲,肩帶結構必須進行重要的適應,沒有其他物種能像人類一樣投擲。看看那些對身體施加極限壓力的投擲運動,所有民族(白人、黑人、亞洲人等)在投擲運動(如棒球、標槍投擲等)中大致產生同樣數量的頂尖表現者,當然,這取決於社會文化影響。

It seems that differences in performance ability in high-speed running are somehow linked to its irrelevance. What then is so irrelevant about running at top speed? The decrease in the dominance of athletes of West African origin as running speed decreases gives an indication, which science is still far from fully understanding. Under time pressure (the support phase lasts less than 0.1 sec), maintaining a (albeit small) horizontal component in the propulsive force. In other words, at speed, there is increasingly less time to exert force backward against the ground shooting beneath the sprinter.

在高速奔跑中,表現能力的差異似乎與其不相關性有某種聯繫,那麼,高速奔跑究竟有什麼不相關的呢?隨著跑步速度的降低,西非血統運動員的優勢減少,這一點提供了一個表徵,科學對於這一點的理解仍遙不可及。在時間壓力下(支撐階段持續時間少於0.1秒),保持一個(雖然很小)水平方向的推進力組件,換句話說,在高速運動中,向後施加力量以抵抗跑步者底下的地面變得越來越困難。

Where do you find individuals suitable for such a niche skill as sprinting? Probably where there is the greatest variation in the composition and interaction of organism components, and the chance mix that we recognize as a super talent is most likely to occur. There you find the ‘outliers’, the extremes, the physical freaks. Those athletes with such rigid tendons that they won’t excel in ice skating or swimming, with a hormonal balance that shuts down all systems halfway up the Cauberg (known as a category 3-4 mountain climb in cycling), with lower legs so long that dribbling with a hockey ball will never work well, and with such muscle specialization that climbing a tree is almost impossible. But who happen to be able to bounce over a hard flat surface of synthetic rubber.

Do West Africans and their descendants in the Caribbean and the US harbor more of such ‘outliers’ than other regions? Perhaps, especially those who have a mix of properties that delay inhibition in high-speed running compared to others.

你在哪裡能找到適合這種專業技能的短跑運動員?可能在有著最多樣化的生物組成部分及相互作用的地方,而我們認為的超級天才最有可能出現的隨機組合。在那裡,你可以找到「離群值」,也就是極端、身體異常的人。那些韌帶非常僵硬,無法在冰上滑行或游泳的運動員,那些荷爾蒙平衡在騎自行車時到達Cauberg坡道 (在自行車運動中被稱為3~4級爬山) 的中途就會停止所有系統的運動員、那些小腿如此之長以至於無法好好曲棍球運球的運動員,甚至擁有如此專業的肌肉結構,以至於幾乎無法爬樹,但他們卻恰好能在合成橡膠的硬平面上彈跳。

西非人及其在加勒比和美國的後裔是否擁有更多這樣的「離群值」,而非其他地區?也許,特別是那些擁有延遲高速奔跑抑制特性的特徵的混合類型。

Finally最後

In addition to biological factors, there are, of course, many other factors at play, usually summarized in socio-cultural influences. To claim that these are more important than the biological factors, as Pitsiladis does, lacks any basis. He emphasizes socio-cultural factors that contribute positively to the performance of black athletes, while forgetting to consider the negative socio-cultural aspects. Sprint training already lacks much proper science; the expertise of coaches in the US, the Caribbean, and West Africa is also astonishingly low. The training some top athletes undergo is sometimes almost laughable, and the idea that they train so hard doesn’t apply to many top athletes. Many top sprinters are notoriously lazy. Athletics is not the highly developed sport it claims to be, just like most sports bluff their professionalism. Moreover, the best coaches are found in a region (Scandinavia, Germany, Belgium, and also the Netherlands) where there is little talent available. They cannot afford to be careless with scarce talent and must make every effort to seek new avenues.

除了生物因素外,當然還有許多其他影響因素,通常被總結為社會文化影響,Pitsiladis表示,宣稱這些因素比生物因素更重要缺乏任何依據,他強調對黑人運動員表現有正面貢獻的社會文化因素,但卻忘記考慮負面的社會文化方面。短跑訓練本來就缺乏足夠的科學支持,美國、加勒比和西非的教練專業知識也非常低落,一些頂尖運動員所接受的訓練有時看起來幾乎可笑,且「他們訓練得如此努力」的觀念對於許多頂尖運動員來說並不適用。許多頂尖短跑運動員 是以懶惰著稱,田徑並不像它所聲稱的高度發展的運動,就像大多數運動都在虛張聲勢其專業性一樣。此外,最優秀的教練通常位於一個(斯堪地納維亞、德國、比利時,還有荷蘭)人才稀缺的地區,他們不能對稀缺人才掉以輕心,必須努力尋找新途徑。

Athletics is the ultimate talent sport. Training too hard easily leads to injury or overtraining (jumpers and sprinters nowadays train much less than in the 1980s), and it is important to train as little as possible but just enough to hit the sweet spot of minimal inhibition.

From the perspective of minimal inhibition, it is more important to maintain and reuse the (elastic and kinetic) energy stored in the musculoskeletal system at speed per stride (not to ‘leak’ energy) than to generate extra energy (power). This is clearly visible in lightly built athletes like Lyles, De Grasse, Lemaitre, and Martina. Dafne Schippers is also an example of this, at least during the years when she was technically superior.

田徑是終極人才運動,太努力訓練很容易導致受傷或過度訓練(如今跳高者和短跑者的訓練量遠低於1980年代),重要的是盡量少訓練,但要訓練足夠,以達到最小抑制的最佳狀態。

從最小抑制的角度來看,在維持每一步的速度下,保持和重用儲存在肌肉骨骼系統中的(彈性和動能)能量(不「洩漏」能量)比產生額外的能量(動力)更為重要,這在體型較輕的運動員身上明顯可見,例如 Lyles、De Grasse、Lemaitre 和 Martina。Dafne Schippers 也是這方面的一個例子,至少在她技術上優越的那些年。

Degeneracy explains another phenomenon: there are multiple ways to shift inhibition. Hence, there can be such different body types at the start of a 100m final. Furthermore, there is another factor that may be even more important for the differences in physique among top sprinters. A 100-meter race is actually a sport consisting of two barely related sports, starting and accelerating, and running at top speed. For the start, it’s useful to be small and compact; for top speed, length is an advantage. So, in a 100-meter race, we’re not looking at a sport of pure speed but a mix of two somewhat opposing requirements. And could West African outliers be the athletes who best combine these opposing requirements within themselves?

退化解釋了另一個現象:存在多種方式來轉移抑制,因此在100米決賽的起跑時,可能有如此不同的身體類型,此外還有另一個因素,可能對頂尖短跑選手的體型差異更為重要:100米賽跑實際上是一項由兩種幾乎不相關的運動組成的運動,起跑和加速,然後以最高速度奔跑。對於起跑,身材小巧緊湊是有利的;而對於最高速度,身高是優勢。因此,在100米賽跑中,我們所看見的並不是純粹的速度運動,而是兩種相對獨立的需求的混合。西非的特例是否是將這些相對需求在自己身上最好結合的運動員?

It is also remarkable that the differences in body build among top endurance runners are much less pronounced. Perhaps this is because aptitude for endurance running did have an evolutionary advantage (see the theories and research of Daniel E. Lieberman). In East Africa, this aptitude has been better preserved than in other regions where humans migrated. Thus, . Conclusions from research into endurance running cannot be extrapolated to conclusions about sprinting.

Who knows, and science is still quite far from the answer. Perhaps it helps if we no longer ask why Usain Bolt can run so fast but start asking why Usain is less slow than the rest.

更值得注意的是,頂尖耐力跑者之間的體型差異要小得多,也許這是因為耐力跑的才能在演化上確實具有優勢(見 Daniel E. Lieberman 的理論和研究),在東非,這種才能比其他遷移區域更好地被保存下來,因此來自該地區的跑步運動員的優勢是基於與演化無關的短跑運動員優勢截然不同的機制,對耐力跑的研究結論不能推廣到短跑的結論。

誰知道?而科學距離答案仍然相當遙遠,或許如果我們不再問為何 Usain Bolt 能跑得如此快,而開始詢問為何 Usain 相對於其他人不那麼慢,或許會有所幫助。

Frans Bosch System Level1 國際師資認證課程:https://forms.gle/M2wJNhvH2uo9YZpL9

Recommended literature 參考文獻

Frans Bosch, Anatomy of Agility, 20/10 Publishers, 2019

Frans Bosch, Frans Bosch, Ronald Klomp, Running, Biomechanics and Exercise Physiology Practically Applied

Daniel E. Lieberman, The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease, Atlas/Contact